Nanbudo is usually defined as an art for the creation of Ki energy, an energy which promotes the harmonious union of the body and mind. The principles of Nanbudo originate in the laws of nature. The objective of this art is to completely liberate the practitioner from his fears and anxieties as this will release his most inner desires and passions. One aim is to show the way (Do, Michi) and thus to encourage a greater understanding of the realities of life and its many forms. The flow of energy (Ki) results in a physical and mental stability and promotes good health (Kenko) and resistance to modern illnesses like stress, mental illness, backaches, etc. The founder of Nanbudo, Yoshinao Nanbu Doshu Soke once formulated this in the following sentence: “Nanbudo, in essence, abolishes all forms of extrovert strength. However, it permits the acquisition of inner strength, which is confirmed each day by a positive attitude in our daily lives. Living is a perpetual renewal of this energy. Let us accept the natural cycle in which we find ourselves, and with all senses alert, let us bind ourselves closely to it. This marvelous sensation is at the basis of our creative force. Nature speaks to us: let us address her, and especially imitate her”.

Founder.

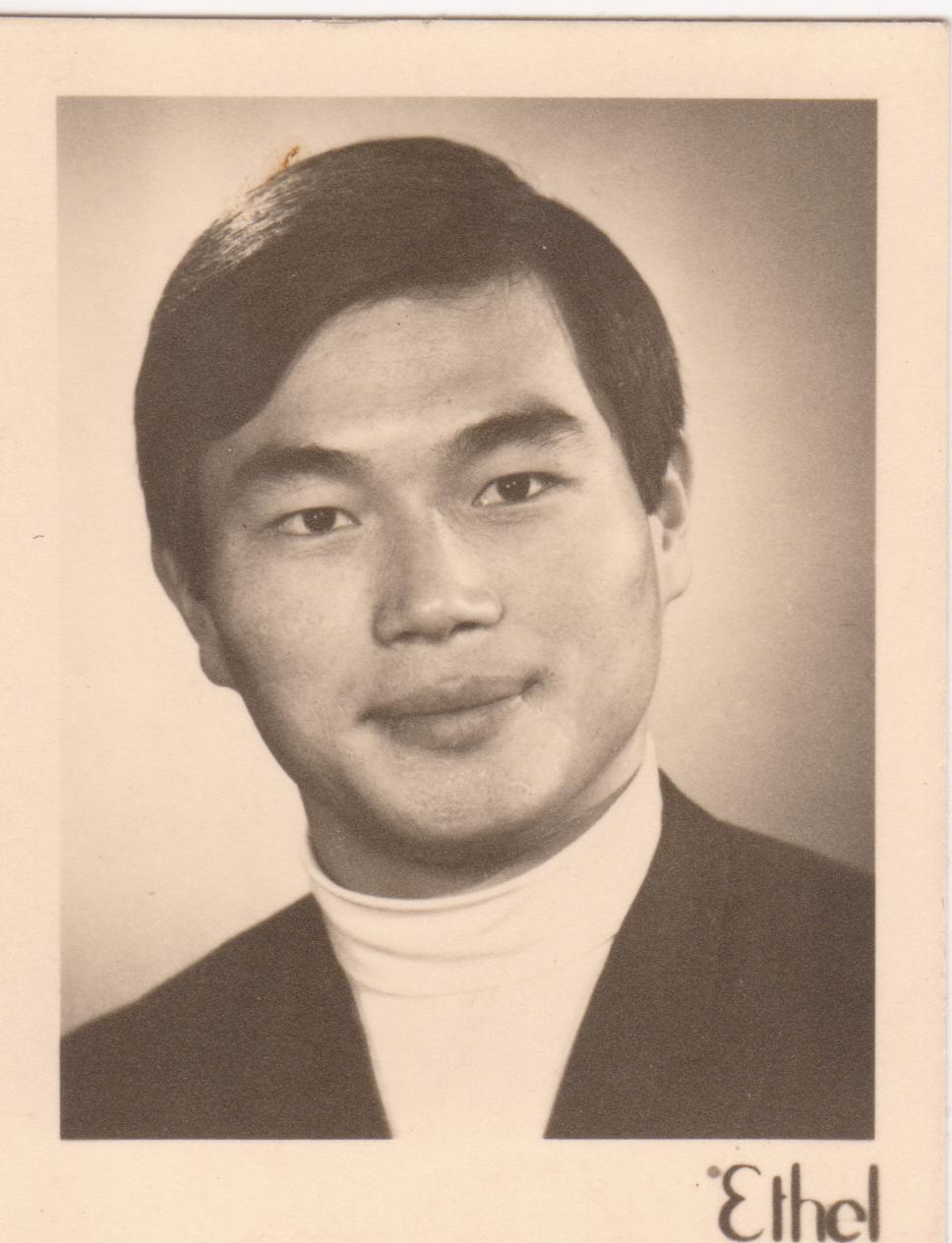

The founder of Nanbudo (Doshu) is Yoshinao Nanbu, born in 1943 in Kobe, Hyogo prefecture, Japan. He grew up in a milieu in which Budo (martial way) was held in high esteem. His great-grandfather was a famous Sumoka (Yokozuna), today covering many pages of Japanese rich Sumo history in Ryokugikan. At the early age of five Yoshinao’s formation as a true martial arts practitioner (Budoka) began with learning Judo in his father’s Dojo, where the American troupes were seldom taught the martial ways of gentleness. After a few years he also began studying old Japanese swordsmanship (kendo, iaido, battodo) from his uncle. At the age of 18, when he was admitted as a full-time student at the University of Economic Sciences in Osaka, he discovered Karate. At that point Shitoryu was the only reasonable option of Karate in Kansai area of Japan, famous for its hard blocks and strict Kata definition. He followed the teachings of Sensei Tani and Tanaka and soon became the best Karateka in Japan. In 1963 he won the title of the All-University Champion of Japan, proclaimed to be the best fighter of the event in which there were 1250 competitors. University Championships, at that point, were the peak-test for all Japanese Karateka, and not only because of the numerous participants but because of the qualities of Karate implementation in the University milieu.

But actually, one French Karateka, Henry Plée (1923-2014) had an enormous influence on Yoshinao’s earliest Karate career. Plée was a pioneer of Karate and All-Japanese Budo as well, in Europe, but especially in France. For many European Karateka he is considered as the ‘father of both European and French Karate’. Henry Plée was the oldest and Karate highest ranking Westerner alive, with more than 60 years of life dedicated to Budo. He was a pioneer in his efforts of introducing Karate styles to France and Europe and has been a teacher and a mentor to most of today’s highest ranking Karateka in Europe. In 1955 he founded his own Dojo: Karate Club de France (KCF), which became ‘Académie française des Arts Martiaux’ (AFAM), later on ‘Shobudo’, also known as ‘Dojo de la Montagne Sainte-Geneviève’ in central Paris. It is one of the oldest Karate Dojo’s in Europe, whose members had won many French, European and World championship titles since its creation. Four basic or fundamental styles of Japanese Budo were taught here: Karate, Judo, Aikido and Kendo. Plée Sensei, at that point, frequently traveled to Japan. There he met with and learnt from some of the most famous Karateka of all Ryu. He invited many of them to visit him in France. One of them was Yoshinao Nanbu Sensei, at that point one of the strongest figures of Japanese Karate, as well as a captain of Japanese Karate Team. They soon became very good friends and for a while Nanbu Sensei was teaching Karate, Judo and Aikido in Plée’s Dojo. Nanbu Doshu often retells stories about his encounters with Mr. Plée, i. e. in Japan where French Karateka was fascinated by the scrutiny and hard trainings of the Kansai styles Karate practitioners, or in France, where he always admired Nanbu Doshu’s energy in teaching and spreading all aspects of Japanese Budo culture. Actually, young Nanbu Sensei invited many Japanese instructors to come to Europe to teach and spread their own styles, s. a. Kamohara, Kimura, Tsukada, to name just a few of them.

At the peak of his competition career Chojiro Tani Sensei asked young Mr. Nanbu to go to France and to spread Shukokai Karate there and in Western Europe. Nanbu Sensei did this with great success. He also entered the French open which he won and the European championships, again wining in his category. He soon became the advisor of the French national team. Henry Plée invited Nanbu Sensei to France because he was impressed by the young champion’s motivation as well as with his unique style of teaching. It should be mentioned that at this point, fortunately, Nanbu Doshu was already modifying some basic movements of traditional Karate Keiko. While in Paris, where Yoshinao Nanbu was a student at Sorbonne, he taught Judo in the morning, Aikido in the afternoon and Karate in the evening in the famous Plée’s Dojo. Plée’s fascination with young Nanbu-san is thus shown in his book from the 1960s with young Nanbu using Ashi-barai sweep in a French Karate final on the front cover.

After winning all gold medals, event after event, such as French Cup or European Championship, etc. young Nanbu returned to Japan in 1968. He wanted to enrich his technique and his knowledge of the way of Budo. Actually during exactly that year, his teacher Chojiro Tani entrusted young Yoshinao Nanbu with the mission of developing Shukokai Karate in Europe. He fulfilled this mission with huge success. But he was already very sceptic towards traditional or even reformed Karatedo doctrine. At 27 years of age Yoshinao Nanbu arrived at such a high degree of skill that he created his own method and called it Sankukai. However, he felt that Sankukai was only a stage in his journey. Nevertheless, he managed to organize several international competitions, both in Shukokai and Sankukai Karatedo. After several disputes with some of his leading students, around 1974 he withdrew completely from the world of martial arts and went to Cap d’ Ail, south of France. There, amidst the natural elements, he was able to meditate and to connect with the true value of things. He discovered the precise path he really believed in: Nanbudo was born.

Since the creation of Nanbudo in 1978 until today Yoshinao Nanbu Doshu is an active teacher. He is constantly developing and refining his art and regularly travels around the world to direct Nanbudo seminars in different countries. The central seminar takes place every summer (July) on the beach of Platja d’ Aro, Spain, thus bringing together many practitioners from all parts of the world in a creative and friendly atmosphere.

Short INTERVIEW.

LR: Which of the experiences from your earliest youth regarding the martial arts you still remember?

YN: One of the most beautiful moments of my youth relates to the trips in the mountainous area of Tajima, during the summer holidays. There I would usually spend the whole summer, swimming, catching fish, enjoying the environment. This essential relationship with nature has shaped my earliest childhood and in some way introduced me in the martial arts world. I later paid tribute to this area of my childhood by creating Kata that is called Tajima, a form that is still practiced in Karate style of Sankukai and in Nanbudo, now called SHIN TAJIMA (New Tajima).

LR: Your entire life is actually related to martial arts. Where are the sources of this interest?

YN: My father and my uncle both taught judo in Japan, in Kansai region, and they were excellent instructors in the traditional sense of the old school judo. Their training methods were very strict as well as the training methods of my first Karate instructor. In the earliest days of my martial arts practice I already knew that I would become a martial arts instructor. I trained many of them, Judo, Karate, Kendo, Iaido, Aikido. At that time I didn’t have a vision of my own style or my own, new, reformed methods, but I had a synthetic mind, when it comes to martial arts. My family was a samurai family, I mean my ancestors, and all my relatives and contemporaries, friends, were closely related to the different martial traditions of Japan – not only to skills that would later overwhelm the West but also with lesser known skills as Jukendo.

LR: What were the training methods in your early days? Can you upload some experience?

YN: The most fresh are my memories of judo trainings that were very demanding, with lots of repetitions. However, great attention was put on to the technique, precision and softness of judo techniques, in the sense that it was first employed by Jigoro Kano. Today, such an approach to judo is almost lost, although it exists, it has been preserved, somewhere deep in the original idea of Judo Randori techniques or Kata. Furthermore, one of my most interesting instructors was Tanaka sensei, an Aikidoka whose teaching methods were specific – in the early stages of learning he would never touch his students with bare hands, and all of the arm-locks and throwing techniques would be performed using a wooden stick. In early youth I had been introduced to aikido, and even watched its founder Morihei Ueshiba demonstrating. I am actually still fascinated by the fluidity of the movements in almost all these Japanese martial arts.

LR: However, you also had a close relation to your teacher Chojiro Tani?

YN: Yes, Tani sensei is one of the Karate instructors who deeply influenced my understanding of martial arts, particularly modern Karate. Although at one point I refused to follow him, this was a conceptual split, even though at that time I was entrusted the mission of development of TANI HA SHITO RYU KARATE in Europe, particularly in France, I could not completely follow his path. Karate at that time had a certain dosage of inflexibility and lack of adaptability that made me more of detached to it than would have made me attracted to his many and great values. I had to go my own way and leaving my teacher Tani was a hard task for me. At a time when we were parting, saying hello, a bottle of sake cracked in his hands. Several months later he died.

LR: How did you decide to go to Europe?

YN: My departure from Japan was not a simple and easy decision. There were a lot of financial and diplomatic obstacles, from the procurement of paper and warranty documents on one hand, to parting with friends, family, etc. on the other. However, it was a good decision, I did not regret it. I got to know a different culture, in which I later founded my family, and out of Nanbudo I made an interculturally recognized and unique art. I also made friends with many Japanese immigrants in France. Life is a unique opportunity and we should not complain even for once, we should be aware of our own mistakes and continue to follow the path. The first years in Europe were very difficult for me. I practiced a lot and had a sort of contract with Henry Plée, French legend of Karate and my patron at the time, to visit as many of the international and national tournaments and championships and to always win. That’s what I did. I taught a lot, which really shaped me as primarily Budo teacher. In the early morning hours, in Paris centre, actually in today’s dojo of Henry Plée, I taught aikido, later on I taught judo in the afternoon and in the evening hours I conducted Karate lessons, almost daily.

LR: In Paris, where you live today, of course, and on many trips, you have met many celebrities, both from the world of martial arts and other domains?

YN: Yes, big names of the Japanese Budo are my friends, from Mochizuki, Kamohara, Nakamura, Nakahashi, to the great ZEN philosopher and writer Taisen Deshimaru. Paris is a great center of martial arts in Europe and all over France, a fertile ground on which many Japanese instructors found their home. With most of them I still intensively socialize, we organize joint seminars and lead a sort of an association of Japanese experts in Europe. French Federation of Karate and Associated Disciplines (FFKDA, Fédération Française de Karaté et Disciplines Associées) recently decided to award myself with the grade of 9th DAN, due to my lifelong achievements in promoting traditional Japanese martial arts and my own way of BUDO in France. Most of the officials in charge of giving this high title to me were actually and paradoxically my first students in the past. Nevermind, this is the highest rank in the federation of this kind and the highest grade to be awarded and approved in France, on which I am very proud.

LR: How has Nanbudo actually created and which intimate causes led to this?

YN: It was created in very unsuitable conditions but in very favorable circumstances, on the other side. Nanbudo flourished in me even in the period when I was in Europe for the first time, spreading a mixture of Shitoryu and Shukokai methods and styles, and later on Sankukai Karate. However, the suitable conditions for presenting Nanbudo to the public were not yet present. The gap and conceptual differences in Sankukai Karate organization led me to my escape in solitude. In 1976, after disagreements with Tani’s concepts, as well as after many conflicts within a large Sankukai Karate family, I finally realized that I should not be satisfied with my newly created style and techniques, which in Europe and Japan had a large number of followers. In the natural environment of Cap d’Ail in southern France I remained until 1978, before finally presenting Nanbudo to general public. I had a big opportunity to demonstrate Nanbudo in front of Prince Rainier and Monaco royal family. During the solitude period I meditated almost every day, rehearsing a variety of principles and forms. It was not a classic isolation like, for example, isolation of a Zen priest – it was more an enrolment to create a positive work environment – and a place for a hard work.

LR: What were the reactions to the new martial art?

YN: Reactions were different. On one hand, they called me thinking machine, because the techniques that I presented to the public were very complex, quite different from the systems that were represented in the most popular martial arts. Some of them, of course, were skeptical. But, in my life I was never served, people have always tested me, ever since my youth. As a captain of Japanese Karate team at the University of Osaka, I was often forced to demonstrate my own authority, even though I was more easygoing in the way of preparing the university team, especially considering MAKIWARA techniques. Even my own father often tested me. Now I would like to only mention one episode, just before my first trip to Paris: I had to agree on performing judo randori with my own father in front of the audience. Luckily I performed a quick and explosive technique IPPON SEOI NAGE, and indeed this symbolic match was recorded by my friends. Once I was even tested by Willy Wallace, who wanted to actually test the effectiveness of Nanbudo principle of simultaneous punches and defense.

LR: What part of Nanbudo is the most complex, in your opinion?

YN: Perhaps the most complex part is KEIRAKU TAISO and KI NANBU TAISO systems, therapeutic forms of energy circulations, primarily because they function as little Kata, small forms, as well as respiratory exercises and meridian therapy. In the combat system of Nanbudo perhaps the most complex are sweeping and throwing techniques, especially the circular sweeping systems, such as KAITEN GERI GEDAN technique, which has become the trademark of Nanbudo as a martial art. When the practitioner enters the system of Nanbudo, of course, he eventually recognizes the purpose of all the elements that are interconnected and, in my opinion, form a unified system.

LR: You often emphasize the importance of individual training, a kind of self-evaluation within the art and within one’s own understanding of Budo. Can you explain that?

YN: This refers to the physical and mental health level. One drop of water does not damage a hard rock, but after a few decades, the stone breaks under the force of water. Rather, the persistence of the water subsides. When I was young I wanted, for example, to strengthen the muscles and speed up the leg kicks wearing GETTA sandals and carrying out hits with them. Every day I would wear them to the university but one day the manager of the train station asked me to stop wearing them – because they were damaging the floors. I would work up to a thousand kicks a day, I would practice hand techniques on MAKIWARA and finally I would use a bicycle tire for training explosive judo throws and Karate punches. Today, of course, that does not work, but I projected this concept of physical work on mental training. Therefore, Nanbudo is a living art: I observe my students during seminars and I modify techniques, transform them, frequently and radically changing my method, introducing new elements into existing and already established system. Otherwise, the metaphors of water is extremely important for my martial art, it lead me in the moments of meditation and during the creation days of Nanbudo, and I often use it today to describe the relaxing mode and naturalness of Nanbudo techniques.

LR: You often emphasize the importance of Kata in development of Budoka.

YN: From the moment I began to teach and study martial arts – that is what I do today, forty years later – I realized the importance of Kata in learning all of the techniques in every kind of Budo. Regularly, I try to convince my students that Kata is foundation of every traditional Japanese martial art. I have devoted great attention to teaching and practicing Kata techniques: in Shitoryu there were hard Okinawa Kata systems to learn, in Shukokai slightly softer, in Judo training the turn for me were the KODOKAN KATA. At a time when I came to Europe the technical base of Karate were the reformed SHOTOKAN KATA, PINAN and HEIAN. In the early stages of Sankukai these Kata were replaced by my own HEIWA KATA systems. HEIWA means peace, and in the beginnings of Sankukai these Kata were actually the equivalent of basic Shotokan, HEIAN and PINAN system. Indeed, the entire catalog of Nanbudo techniques today actually revolves around the idea of form, precisely specified sequence of techniques, without deviations. All aspects of Nanbudo, from martial (BUDOHO), to its energy (KIDOHO) and mental bases (NORYOKUKAIHATSUHO) actually focus on the training forms. There is nothing in Nanbudo that exists outside of form-systems, which is why most martial arts connoisseurs stand fascinated in front of the disciplined nature of Nanbudo, as well as in front of its precision. Kata is thus a prerequisite for the existence of basic learning, necessary for the so called catalog of techniques for transferring (MENKYO). System of Nanbudo techniques at the same time disciplines body (TAI) and mind (SHIN), because the students are thus forced to think categorically, orderly and systematically. In Sankukai Karate this mental or cognitive side – and in Nanbudo it is called NORYOKUKAIHATSUHO and is understood as self-development (SHUGYOHO) – was completely ignored. I worked on that mental awareness of Nanbudo, so this actually represents a shift away from traditional Karate which I belonged to, although I still appreciate it immensely.

LR: Nanbudo as a martial art is alive thanks to you. You are constantly traveling and giving seminars around the world. How come you’re not tired?

YN: Positive energy that comes out of my students gives me strength, all over the world, from Cameroon and Ivory Coast to Norway, Finland, France, Spain, Morocco, Hungary, Slovenia and Croatia, to mention just some of them. Nanbudo is often defined solely as ‘an art for creation of Ki energy’, although this may seem a bit fashionable, considering the spread of modern alternative methods. But Nanbudo really awakes the positive side in human beings, because it emphasizes the communication within the movement, because it is fluid and open, because it allows customization, and its wide range of techniques makes it suitable for all. Martial arts should not forget their origin in nature (SHIZEN) and should not function at the expense of nature and natural law. Nanbudo, in its essence, removes virtually all forms of external strength and simultaneously allows the acquisition of internal strength, strengths which are daily confirmed by a positive attitude, positive action. This is the core essence of Nanbudo, which lies in everyday practice, in daily process of acquiring confidence, in the process of precise reasoning, in gentleness towards others.